Well, I finished reading the book a month or so ago, and I suppose I could go back and review the last chapters and try to say something about them, but I don't think I will. I don't really care at the moment.

While I find some pieces of the book interesting and helpful, as a whole I find it kind of disappointing. I think this has a lot to do with the style of the book: There's a lot of meandering and poking into myths and dream stories, which produces some nice, lyrical paragraphs, but there's not a lot of wrapping up or analysis ... at least none that sticks with me as useful or viable. I don't feel like it's significantly changed the way I think about the world. Maybe, though, that has to do with how much time and thought I've put into the book. Maybe I'm expecting the analysis to be done for me, when this book presents itself as sort of loosely-bound, and expects me to do the analysis myself. Or maybe I can find a few interesting questions elicited by the book, and let those ends dangle for future investigation.

I think that for me, the most interesting questions that the book asks are about meaning-making. I think we agree with Campbell's implication that stories are important to people, and that the things we tell stories about must somehow be tied into human nature, because the same themes keep popping up in stories all around the world. We can also probably agree that these stories are somehow related to big, abstract things like our societal values and subconscious desires.

But what happens if these worldview-grounding stories lose their credibility? What happens if they come to be perceived as uninteresting, or even as false? Will human nature demand that other stories take their place? Will we lose a sense of what things mean? Will we find some way to understand stories as both true and false, demystifying it while still preserving its power?

For help, I should probably read that last section again before I return my month-overdue, out-of-renewals book. But even if I do, I figure this is my last post on HWTF.

Farewell, book!

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

Thursday, December 9, 2010

Virgin Emanations

While Campbell has spent much of the first half of the book describing the process of the hero's quest in mythology, the second portion, so far, has hashed out some of the more fascinating universal elements of mythology to me. Namely, in the first chapter "Emanations" of the second section of the book "The Cosmogonic Cycle" Campbell's analysis of myth has moved from the individuals of mythology to the structure of the whole.

Campbell begins the section with a discussion about the psychological nature of mythology, again relating myth to modern psychoanalysis, because of the connection he sees between dream imagery and mythology. The Universal Round especially embodies, to Campbell, the structure of life dreaming and waking, back and forth eternally. So go the cycles of mythological stories, the universe arises from chaos/void, assumes orderly and beautiful life, reaches a zenith, slides into dissolution, extinguishes into void, long silence, then begin again, to infinity.

This repetitious structure is quite beautiful in a strange and tragic way, but also very bizarre to me. When watching movies or reading books, I watch closely for two different underlying attitudes. One is an attitude in which the story takes itself seriously (i.e. it believes in fairies and knights and dragons and evil emperors), the second thinks of its characters and settings as vehicles for communication, with only a thin layer of effort to pump life and thought into its constituent parts. This, for me, is a major difference between good and bad narrative art. The best artists are the ones who believe in their work, who give their characters weight and thought and emotion and reality.

Hayao Miyazaki, my favorite filmmaker and an excellent narrative artist, portrays characters with striking reality. But, their reality is not in their looks, but in their actions and attitude. His films show characters constantly in the full-swing of life: they run, they dig, they climb, they cook, they eat, they tire, they sleep, they wake up and start all over. Even when they have internal conflicts, the films never belabor this, but exhibit their struggles by their responses and their interests. It is the old adage of filmmakers and dramatists, "Show, don't tell!" And, honestly, it is completely true. Showing a man have difficulty in deciding on which entree to order is MUCH, MUCH better than telling the audience that he's indecisive. While the telling may be a short hand to communicate information, showing gives a forceful impression of how a character moves and feels. It gives him the ring of truth.

This thought about hard versus psychological readings of stories keeps ringing in the background of my head. Campbell implicitly includes religions in his examples of mythology, but often repeats the problems of interpreting any of these collective stories as historically accurate; he sees them as stories we measure our lives against, as vessels to communicate values and truth. Yet, if the best narrative art is that which is believed in its telling, where the characters have a reality to them, where do belief and story meet? If it is not to be simply as a dry, pedantic blue-print for life, nor a codified encyclopedic set of historical realities, where does it fall in the middle?

To that extent, perhaps it burns somewhere between the two, in a dark forest. We catch but a whisper of its light the tree and snow, but only catch up to have it vanish before we arrive.

Most theists I know are not deeply concentrated on life-long searches for undeniable evidence for the existence of God, or for historical and geological evidence to uphold claims about the history of the world and who died and who rose. But, that is not to say they are wrong, it is to say that perhaps we simply lose our focus on what's most central. For it seems to me the central concerns of religion are spiritual formation, communal peace, justice and joy-filled life, not historical reality. So, where again is the meeting place of life and story, life and mythology?

Other thoughts from these chapters: the neo-Platonist in me likes the idea of creation as a vast emanation of a grand, central being. The sculpture in Plate XX of "Tangaroa, Producing Gods and Men" is quite striking. The image of beings contorting from the essential fabric of the universe (which is the skin and organs of the great creator him/herself) is a beautiful notion of creation. It reminds me of John.

This panentheistic notion of the world's conception inside of God himself is an eloquent rendering of life, and a great way for giving an uplifting and hopeful image of a universe that can be at once beautiful and ferocious (God as Creator and Destoyer... of self?).

In the Hindu myth, she is the female figure through whom the Self begot all creatures. More abstractly still, she is the lure that moved the Self-brooding Absolute to the act of creation.

This seems a projection of procreation. Let us move forward.

Campbell begins the section with a discussion about the psychological nature of mythology, again relating myth to modern psychoanalysis, because of the connection he sees between dream imagery and mythology. The Universal Round especially embodies, to Campbell, the structure of life dreaming and waking, back and forth eternally. So go the cycles of mythological stories, the universe arises from chaos/void, assumes orderly and beautiful life, reaches a zenith, slides into dissolution, extinguishes into void, long silence, then begin again, to infinity.

This repetitious structure is quite beautiful in a strange and tragic way, but also very bizarre to me. When watching movies or reading books, I watch closely for two different underlying attitudes. One is an attitude in which the story takes itself seriously (i.e. it believes in fairies and knights and dragons and evil emperors), the second thinks of its characters and settings as vehicles for communication, with only a thin layer of effort to pump life and thought into its constituent parts. This, for me, is a major difference between good and bad narrative art. The best artists are the ones who believe in their work, who give their characters weight and thought and emotion and reality.

Hayao Miyazaki, my favorite filmmaker and an excellent narrative artist, portrays characters with striking reality. But, their reality is not in their looks, but in their actions and attitude. His films show characters constantly in the full-swing of life: they run, they dig, they climb, they cook, they eat, they tire, they sleep, they wake up and start all over. Even when they have internal conflicts, the films never belabor this, but exhibit their struggles by their responses and their interests. It is the old adage of filmmakers and dramatists, "Show, don't tell!" And, honestly, it is completely true. Showing a man have difficulty in deciding on which entree to order is MUCH, MUCH better than telling the audience that he's indecisive. While the telling may be a short hand to communicate information, showing gives a forceful impression of how a character moves and feels. It gives him the ring of truth.

This thought about hard versus psychological readings of stories keeps ringing in the background of my head. Campbell implicitly includes religions in his examples of mythology, but often repeats the problems of interpreting any of these collective stories as historically accurate; he sees them as stories we measure our lives against, as vessels to communicate values and truth. Yet, if the best narrative art is that which is believed in its telling, where the characters have a reality to them, where do belief and story meet? If it is not to be simply as a dry, pedantic blue-print for life, nor a codified encyclopedic set of historical realities, where does it fall in the middle?

To that extent, perhaps it burns somewhere between the two, in a dark forest. We catch but a whisper of its light the tree and snow, but only catch up to have it vanish before we arrive.

Most theists I know are not deeply concentrated on life-long searches for undeniable evidence for the existence of God, or for historical and geological evidence to uphold claims about the history of the world and who died and who rose. But, that is not to say they are wrong, it is to say that perhaps we simply lose our focus on what's most central. For it seems to me the central concerns of religion are spiritual formation, communal peace, justice and joy-filled life, not historical reality. So, where again is the meeting place of life and story, life and mythology?

From NASA's Godard Space Flight Center"The illustration maps the magnetic field lines emanating from the sun and their interactions superimposed on an extreme ultraviolet image from the Solar Dynamics Observatory on October 20, 2010. "

Other thoughts from these chapters: the neo-Platonist in me likes the idea of creation as a vast emanation of a grand, central being. The sculpture in Plate XX of "Tangaroa, Producing Gods and Men" is quite striking. The image of beings contorting from the essential fabric of the universe (which is the skin and organs of the great creator him/herself) is a beautiful notion of creation. It reminds me of John.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning.

Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made. In him was life, and that life was the light of men.

This panentheistic notion of the world's conception inside of God himself is an eloquent rendering of life, and a great way for giving an uplifting and hopeful image of a universe that can be at once beautiful and ferocious (God as Creator and Destoyer... of self?).

Virgin births: I'm not sure that I feel deeply struck by this. Campbell abstracts in this section, as you can see below.

In the Hindu myth, she is the female figure through whom the Self begot all creatures. More abstractly still, she is the lure that moved the Self-brooding Absolute to the act of creation.

This seems a projection of procreation. Let us move forward.

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

Of Returning Keys

I think you covered the overview well of these two chapters. I really enjoyed the Shinto myths of Amaterasu and then the myths of Izanagi and Izanami. Actually, what this made me think of a lot was a PS2/Wii game called Okami. It's an excellent game with a beautiful visual style that puts some different spins on some of the Shinto myths regarding Amaterasu. You play as Amaterasu incarnate as a white wolf, battling demons with the Shinto mystic relics of sword, beads (rosary) and mirror to restore natural beauty and peace to Japan. Also, it incorporates a kind of ink brush drawing interface for a portion of the game play that you must use to defeat enemies and solve puzzles.

Also, I found the story of Arjuna from the Bhagavad Gita. A fascinating image of a man perceiving the infinite in a short moment on the battlefield, "the moment just before the blast of the first trumpet calling to combat." I like ideas/stories like this when a character glimpses through a small crack in time the great chasm of eternity beyond, and it forever changes the individual. Another association: Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, my favorite jazz, rock, bluegrass, fusion band, did a song about this little story, or at least a kind of interpretation called "Sojourn of Arjuna" complete with some great bass, banjo and sax solos. Unfortunately, I couldn't find a version with the full lyrics, this one is more of a prolonged jam, but in the studio version Future Man has several verses of narrative and exposition.(Bela Fleck on banjo, Jeff Coffin on sax, Victor Wooten on bass and Future Man on vocals and electric drums.

One of the other interesting quotes from "Master of Two Worlds" involved the nature of embodying the Cosmic Man in an identity reflective of the storyteller:

To extrapolate further, it seems by looking at people's interpretations of divinity, of God, we see much about who they are and how they look at the world. Your perception the divine's incarnate tendencies affects how you think about life, destiny and morality. It's a simple, but powerful thought. I guess the question to me is always: can we change how we view divinity? If we grow up with a certain view of God, only to find that it's a flawed view, can you change it for a better fuller one without losing the conception altogether? I think it's possible, but I think it's difficult. This shaping of one's perception of God is that point of having your own faith, or stepping beyond the childhood images of God come from parents and authority figures and basing your vision on experience.

Concerning your point about symbolism and God, I see where your coming from, but I also feel like there's something to having multiple, even diametrically opposed symbols, for someone or something. For instance, God as creator and destroyer on the face are opposite interpretations, but they both do place God as in power over the world, and thus, in a similar identity. It makes me think about value contrast in drawing, where you create a continuum of lights and darks from black to white, basically, and it's the proper placement of these that can create the illusion of depth, definition and form on a 2d surface. So, though the shadow and highlights might be conceptual opposites, it is this very tension that, orchestrated properly, creates definition and, if you will in an illusionistic, pictorial sense: truth.

Perhaps having logically opposite symbols for God is also symbolic in literary form. It is a symbol to show God's fullness with a nature that is beyond definition. Dostoevsky was an author famously praised by the literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin for writing characters in polyphonic voice. Essentially, Bakhtin argued that Dostoevsky's characters were so successful because of their inner multiple-voiced identities. In a Dostoevsky novel, a single character will constantly have multiple desires, competing goals and seemingly irrational tendencies/thoughts. Granted, Dostoevsky himself was vaguely crazy, but these inner contradictions often give a sense of a full-fledged personality, complete with the inconsistencies of human nature.

Also, I found the story of Arjuna from the Bhagavad Gita. A fascinating image of a man perceiving the infinite in a short moment on the battlefield, "the moment just before the blast of the first trumpet calling to combat." I like ideas/stories like this when a character glimpses through a small crack in time the great chasm of eternity beyond, and it forever changes the individual. Another association: Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, my favorite jazz, rock, bluegrass, fusion band, did a song about this little story, or at least a kind of interpretation called "Sojourn of Arjuna" complete with some great bass, banjo and sax solos. Unfortunately, I couldn't find a version with the full lyrics, this one is more of a prolonged jam, but in the studio version Future Man has several verses of narrative and exposition.(Bela Fleck on banjo, Jeff Coffin on sax, Victor Wooten on bass and Future Man on vocals and electric drums.

One of the other interesting quotes from "Master of Two Worlds" involved the nature of embodying the Cosmic Man in an identity reflective of the storyteller:

Furthermore, the revelation recorded in "The Song of the Lord" was made in terms befitting Arjuna's caste and race: The Cosmic Man whom he beheld was an aristocrat, like himself, and a Hindu. Correspondingly, in Palestine the Cosmic Man appeared as a Jew, in ancient Germany as a German... The race and stature of the figure symbolizing the immanent and transcendent Universal is of historical, not semantic, moment...

To extrapolate further, it seems by looking at people's interpretations of divinity, of God, we see much about who they are and how they look at the world. Your perception the divine's incarnate tendencies affects how you think about life, destiny and morality. It's a simple, but powerful thought. I guess the question to me is always: can we change how we view divinity? If we grow up with a certain view of God, only to find that it's a flawed view, can you change it for a better fuller one without losing the conception altogether? I think it's possible, but I think it's difficult. This shaping of one's perception of God is that point of having your own faith, or stepping beyond the childhood images of God come from parents and authority figures and basing your vision on experience.

Concerning your point about symbolism and God, I see where your coming from, but I also feel like there's something to having multiple, even diametrically opposed symbols, for someone or something. For instance, God as creator and destroyer on the face are opposite interpretations, but they both do place God as in power over the world, and thus, in a similar identity. It makes me think about value contrast in drawing, where you create a continuum of lights and darks from black to white, basically, and it's the proper placement of these that can create the illusion of depth, definition and form on a 2d surface. So, though the shadow and highlights might be conceptual opposites, it is this very tension that, orchestrated properly, creates definition and, if you will in an illusionistic, pictorial sense: truth.

Perhaps having logically opposite symbols for God is also symbolic in literary form. It is a symbol to show God's fullness with a nature that is beyond definition. Dostoevsky was an author famously praised by the literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin for writing characters in polyphonic voice. Essentially, Bakhtin argued that Dostoevsky's characters were so successful because of their inner multiple-voiced identities. In a Dostoevsky novel, a single character will constantly have multiple desires, competing goals and seemingly irrational tendencies/thoughts. Granted, Dostoevsky himself was vaguely crazy, but these inner contradictions often give a sense of a full-fledged personality, complete with the inconsistencies of human nature.

Thursday, November 11, 2010

Returning the Keys

OK, so the next sections were:

Chapter III: Return

It's time for the hero to return to the world with his prize.

1. Refusal of the Return

Buuut sometimes he'd rather stay.

2. The Magic Flight

Other times there's something chasing him, and he has to cleverly escape.

3. Rescue from Without

And other times, someone has to come in there and get him.

4. The Crossing of the Return Threshhold

So he crosses back into the world, charged with otherworldy energy.

5. Master of two Worlds

He appears to his followers dressed in the horrible majesty of the other world.

6. Freedom to Live

I really don't know what Campbell is trying to say here.

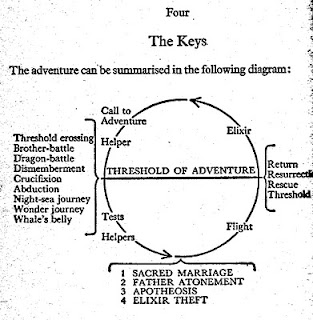

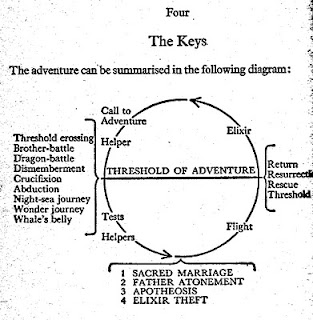

Chapter IV: The Keys

Campbell draws us a picture of the monomyth. He says that the myths have changed over time, and so the core, powerful, monomythic symbols are often buried under a mountain of "secondary anecdote and rationalization."

And that's basically all there is to it. As far as reflection on these sections ...

I drove back from a concert in Dallas today, and during the drive spent a while thinking about symbol and reference. Note this editorial by Campbell, in the section "Master of the Two Worlds":

I like this sentiment, but I also find myself kind of skeptical of it. Sure, I'll buy that God, whatever God is, is so immense that it will overflow any set of symbols we use to represent it. But at the same time, there seem to be issues of logic and paradox that can't be simply whitewashed with an appeal to "mystery". To use examples that appears frequently in this book: is God light, or is God darkness? Is God creator, or destroyer, or both ... and if both, how is that possible? Does the ego survive death, or does it not? If the mythical symbols point to real things, then where the symbol deviates from the thing it references, it would seem to become obfuscating, and possibly deceptive or downright false.

Chapter III: Return

It's time for the hero to return to the world with his prize.

1. Refusal of the Return

Buuut sometimes he'd rather stay.

2. The Magic Flight

Other times there's something chasing him, and he has to cleverly escape.

3. Rescue from Without

And other times, someone has to come in there and get him.

4. The Crossing of the Return Threshhold

So he crosses back into the world, charged with otherworldy energy.

5. Master of two Worlds

He appears to his followers dressed in the horrible majesty of the other world.

6. Freedom to Live

I really don't know what Campbell is trying to say here.

Chapter IV: The Keys

Campbell draws us a picture of the monomyth. He says that the myths have changed over time, and so the core, powerful, monomythic symbols are often buried under a mountain of "secondary anecdote and rationalization."

And that's basically all there is to it. As far as reflection on these sections ...

I drove back from a concert in Dallas today, and during the drive spent a while thinking about symbol and reference. Note this editorial by Campbell, in the section "Master of the Two Worlds":

Symbols are only the vehicles of communication; they must not be mistaken for the final term, the tenor, of their reference. No matter how attractive or impressive they may seem, they remain but convenient means, accomodated to the understanding. Hence the personality or personalities of God -- whether represented in trinitarian, dualistic, or unitarian terms, in polytheistic, monotheistic or henotheistic terms, pictorially or verbally, as documented fact or as apocalyptic vision -- no one should attempt to read or interpret as the final thing. The problem of the theologian is to keep his symbol translucent, so that it may not block out the very light it is supposed to convey.

I like this sentiment, but I also find myself kind of skeptical of it. Sure, I'll buy that God, whatever God is, is so immense that it will overflow any set of symbols we use to represent it. But at the same time, there seem to be issues of logic and paradox that can't be simply whitewashed with an appeal to "mystery". To use examples that appears frequently in this book: is God light, or is God darkness? Is God creator, or destroyer, or both ... and if both, how is that possible? Does the ego survive death, or does it not? If the mythical symbols point to real things, then where the symbol deviates from the thing it references, it would seem to become obfuscating, and possibly deceptive or downright false.

Tuesday, November 2, 2010

Regarding Initiation

Alright, initiation! Penis snakes! Wooooo!

Alright, initiation! Penis snakes! Wooooo!I feel like my posts have been mostly talking past yours, so this time I'm going to do a different thing and try to really focus on the things in this section that you've already talked about ... except for maybe a couple of things that I dog-eared and just can't pass up.

First, I agree. Long chapter. And to be honest, it took me a really long time to read, probably because at this point, I'm having a hard time caring. I just have this feeling that I'm going to get to the end of the book and just sort of sit there, blinking at it, kind of disappointed, thinking, "That's it?"

There's just all of this piling on of myth and symbol and psychoanalysis, and while the similarities between all these things are interesting, I'm having a hard time teasing out Campbell's "theory" based on what I've read so far, or even really understanding what the theory might be about. So far it looks a lot like "see what happens when I interpret Western myth in terms of Buddhist myth!?", but of course there must be more to it than that.

Anyway, enough grouching. You had some interesting things to say.

Who are our "medicine men" today? Who among us "fight the demons" so that we may "fight reality?"

I think this is done is by giving us stories and rituals that we can use to safely raft down the dark rivers of our subconscious. (I don't really know how to use this word correctly in a technical sense, but what I mean is the things that motivate us, but of which we aren't aware.)

To a large degree, I'm going to have to give the "medicine man" distinction to religious leaders. The stories that they tell about the universe, and our place in it, are the only ones big enough to quiet the demons of our deepest selves. And I'd include the New Atheists in this group as well, because they do the medicine-man thing just as well as your standard religious leader, or perhaps better: "I've thought about this already, so you don't have to do any thinking ... just trust me that this is the way things are."

However, I think that some of us are currently operating without medicine men, which strikes me as a fairly inefficient if not dangerous way to go about things. We don't entirely buy the Big Story that our society embraces, which leaves us somewhat adrift. Or as Campbell might say, lost in "the crooked lanes of [our] own spiritual labyrinth."

"Then he finds that he and his opposite are not of differing species, but one flesh." ... This makes me wonder about our interpretations of spiritual rebirth within the church. So often the dialogue centers on rejecting an old self, a kind of aggressive pushing away of a past or a still disappointing present self, rather than a whole and full acceptance of a new self.

I am inclined to agree with your implicit criticism of this approach, initially because I prefer the positive formulation (accepting the new) to the negative (rejecting the old). But also, I think it's because this idea of swapping selves via magic is fairly unhelpful, because it's not really the way things usually work. Certainly, moments of "seeing clearly" can rearrange our perspective, like you mention, but the actual, meaningful change, the one where we start treating the waiter or cashier like human beings, comes a bit at a time and as a habit, not like a magic, transmogrified self.

But I'm kind of hesitant about this, and could be convinced otherwise. Does it make sense to talk about a New Self sort of change? Could it be that it is exactly this story, about the Old Self and the New Self, that works its wonders down deep in our mental hardware and actually makes it possible for us to change from Old to New?

As the hero continues through his trials, he is sure to meet the goddess.

This section troubles me, not because of any well-thought-out objection, but because its gender language seems kind of musty. The binary man-ness and woman-ness implicit in the forms is questionable, and the patterns "man is born of woman, man pursues woman, the hero is male", while probably true for many people and societies throughout history, seem more tenuous now. I would be interested to hear a feminist reading of this section, as well as Woman as Temptress.

The majority of our conscious existence is spent simply perceiving.

I think this is a really interesting observation. So interesting all by itself that I can't think of anything to add.

Clearly, not everyone is vexed with the trouble of having to constantly turn down overly zealous attractive women.

But man, if you do have the problem, it's a vexing one!

Nevertheless, every failure to cope with a life situation must be laid, in the end, to a restriction of consciousness.

You appear to interpret this in terms of Socrates, which I think is warranted: To know the good is to do the good. (And as a corollary useful for judgmental people like myself, "People are doing the best they know how.")

I think there's a different flavor to what Campbell is claiming here, though. I think what he's talking about not employing myth to explain the world, or the right action in circumstance x, but the Buddhist idea of Enlightenment. Enlightened persons, he suggests, are the ones who diffuse both wars and temper tantrums. And I think that for him, enlightenment has a lot to do with the dissolution of selfish desires and the recognition that everything is one.

I think there's a lot to be said for this claim -- Paul Martin's Original Faith, for example, makes a very explicit case that what Buddhism teaches is the deconstruction of the ego, and that once we have sufficiently worked through our own self-obsession, a new and beautiful world becomes available. (Original Faith is out of print at the moment, but hopefully will be back in soon).

Frankly, I like Martin's treatment of this idea better than I like Campbell's, maybe because it's more straightforward. And because it gives some of the practical suggestions you mention, including ways of approaching conflict in the world, sitting meditation, etc. To me, this suggests that myth alone is not enough, or at least it cannot merely be heard or seen, but must be acted on (or acted out) somehow, as with the aboriginal rituals, if it is to be effective.

It seems that at this point, one does not have to fear the loss of his or her identity, because what dwells within and beyond are the same bountiful and beautiful greatness ... I admit that I'm getting rather vague here, as Campbell himself does, but it seems to be true of the greatest and most compelling stories.

Something I've been noticing for a while is that many of the greatest and most useful stories about the world operate at a very high level of abstraction. Certainly, there are many interesting things about reducing the world to its constituent parts, and investigating and chronicling the highly predictable behavior of things like pebbles or molecules or quarks. And learning these things allows us to engineer a world that is more to our liking.

But there are things in the world that are too big and messy for us to reduce in this way, and which are just as real. And it's here that myth and religion and philosophy help us, precisely because they operate at the rarified and often suspiciously ephemeral levels of "ethics" and "metaphysics" and "snake gods". I think you're being broad rather than vague, and I think that broadness is extremely important, and something you shouldn't feel obligated to apologize for.

Thus, for the transcendent hero, the universe itself has been completely shifted and raised to a higher aesthetic level.

The word "aesthetic" here intrigues me. I wonder, what does aesthetics have to say about our status as perceivers, and what language does it use to tell the story of the hero, moving from ugliness to beauty?

Totem, tribal, racial, and aggressively missionizing cults represent only partial solutions of the psychological problem of subduing hate by love ... the individual becomes dedicated to the whole of his society. The rest of the world meanwhile (that is to say, by far the greater portion of mankind) is left outside the sphere of his sympathy and protection because outside the sphere of the protection of his god.

I think it's awfully generous for Campbell to give these evangelical groups the status of "partial solutions", but I also find it difficult to discount them entirely. Thinking in particular of the Christian West: it's obviously gotten something right, as argued by David Bentley Hart and others, but still seems terribly preoccupied with its own vision of the metaphysical machinery of the universe: "God is shaped like this, and relates to the universe like this, and we have to do this to get these souls saved." And because of this preoccupation, or maybe because of a powerful attention to the value of the individual and a belief in the eternal persistence of the individual, it seems entirely blind to the problem of the illusory self. Which I find completely frustrating. It's as if the big pieces we need to live loving lives are split among the world religions. It's like the problem is so big that there is no one story that can contain its solution.

And maybe that's what Campbell is alluding to here, in one of the sections I dog-eared:

It is obvious that the infantile fantasies which we all cherish still in the unconscious play continually into myth, fairy tale, and the teachings of the church, as symbols of indestructible being. This is helpful, for the mind feels at home with the images, and seems to be remembering something already known. But the circumstance is obstructive too, for the feelings come to rest in the symbols and resist passionately every effort to go beyond. The prodigious gulf between those childishly blissful multitudes who fill the world with piety and the truly free breaks open at the line where the symbols give way and are transcended.

But how unsatisfying! First, because Campbell's analysis seems deeply broken: we can't transcend the symbols, we can only deconstruct them, trade them for different ones.

But more than that, this section is frustrating because the dark side of our "childish bliss" is childish petulance, self-absorption, cruelty and hatred. And if the light of knowledge is only available to a small group of "truly free", isn't it a terribly feeble and pitiful light? If this is the nature of the saintly virtue -- to only be accessible to a lucky few -- then perhaps we should abandon it for a more democratic light, one that is not so remote, one that can be accepted by the multitudes, one that allows us all to become truly good.

And the last thing that my mind latched onto was this (quoted from the tao te ching):

All things are in process, rising and returning. Plants come to blossom, but only to return to the root. Returning to the root is like seeking tranquility. Seeking tranquility is like moving toward destiny. To move toward destiny is like eternity. To know eternity is enlightenment, and not to recognize eternity brings disorder and evil.

I'm very interested in the idea of transience -- not just as something that is accepted stoically, but as a value, something that is valued in and of itself. Where a thing is beautiful or good, not in spite of its fleeting nature, but precisely because it is passing. I'm not sure whether people can operate in this way, but I wonder what would be the implications if we could.

That's why this passage from the tao te ching is so interesting to me. The flow of ideas somehow seems to roll along like the flow of things:

Everything is change, life moves down into the earth, into death and the heart of things, rest and tranquility, and into accepting that the world can be no way other than the way it is, flowing forever into eternity. Failing to accept this about the world scatters and destroys, fills the world with unnecessary grief, and unmakes good things before the time for them to be unmade.

Sunday, October 24, 2010

Into the (Circumcising) Flames: Initiation

Though I thoroughly enjoyed this chapter, I must say that it's quite large. "Initiation" is one quarter of Campbell's Hero With a Thousand Faces, and boasts a significant number of discussion-generating quotes and ideas. To review, we've got the general structure of the hero's quest in order, the hero has answered the call, departed from home and now gets into the fray of the quest itself. Initiation discusses the main categories of trials the hero faces on his journey, and unearths how these situations relate to his deeper struggles to come to full maturity.

There is so much in this chapter, that I feel somewhat daunted at the idea of summing up my thoughts on it. I admit that the last two sections are my favorite with the second and third not too far behind. I'll deal out by sub-chapters centering discussion around quotes from Campbell.

1. The Road of Trials

Though this section helped set up the rest of the chapter, I feel as though this was also perhaps the least interesting of the subsections. After opening the chapter, Campbell recounts the tale of Psyche's trials to gain Cupid. This portion reminded me of reading C.S. Lewis' Till We Have Faces, the other year, and what an excellent and fascinating a reshaping of the myth it was. That's a bit of an aside. From Campbell's description, we understand the gist: hero's go through trials and tests to attain their goals.

Despite the simple transfer of information about hero's trials, I found several of Campbell's claims rather fascinating, for one the following concerning medicine men:

Who are our "medicine men" today? Who among us "fight the demons" so that we may "fight reality?" I suppose one could argue that preachers and religious teachers might play a similar role, but I feel they're role has shifted over the years out of this dramatic category of action, and more into the role of the helper, of the guide attempting to help point people in the right direction when they feel confused. Also, religious concerns have branched in the modern age, and now often include the questions of the religion's validity. I think this has largely occurred because knowledge about other religions and about explanations of how the natural world work have been cast, by some, into contention with how one views the structure and validity of his religious beliefs.

I am aware that there have been dissidents of religious factuality in all ages, with recorded skepticism coming from as far back as the pre-Socratic philosophers. But, I also feel as though this trend has come to a head since the Enlightenment. Because scientific systems of thought have been so highly prized, there has been an attempt to require of religious belief the same structure of empirical evidence to prove its "truth." Some have attempted to answer this challenge by advancing a system of admitted irrationality, claiming it is faith itself in the face of reason that is the heart of true belief. Yet, this seems to miss the point, as it attempts to play in a league it was never supposed to be in, like a dance team being forced to play football to prove they are good dancers. It's nonsensical. Campbell's argument, on the other hand, is that the stories were never meant to be taken factually, because they hold implications for how we should live, rather than indications of what exactly did or did not occur in antiquity. I must say that I find this point rather compelling.

On to the next fascinating quote:

Campbell returns again and again to this image of the myth as a spiritual guidepost, a language for encountering and moving through life. Though the process seems one that is, in many ways, intellectual and introverted in our society, he frames it within epic proportions. I say that I rather agree with Campbell's mentality. Finding one's place in life seems to be a steady adventure in the interior of soul, no matter the level of physical activity involved.

One descends into the self to encounter and move past self. This is a central motif of the chapter, the kind of "second birth" that takes place within one to reach a new level of maturity.

Finally, the following quote seems to sum up very well the first section and set the tone/theme for the rest of the chapter with the claim of the cyclical realization of oneness within duality:

This makes me wonder about our interpretations of spiritual rebirth within the church. So often the dialogue centers on rejecting an old self, a kind of aggressive pushing away of a past or a still disappointing present self, rather than a whole and full acceptance of a new self. The kind of death and birth of Christ himself, one where the hero is led silently to the slaughter. He allows himself to be subsumed and in this obedience, this emptying of self, he achieves a new grasp and way of life itself. It is a the true union within the self that is important. More on this in Apotheosis.

2. The Meeting with the Goddess

As the hero continues through his trials, he is sure to meet the goddess. Campbell claims she is the symbol of the remembered mother and the future bride. She can be kind or she can be fearful, she helps either bring together life or destroy it.

Woman, in mythology, as gateway to freedom and universal comprehension. This again fits with the theme of freedom and oneness in duality in the last quote from Road of Trials. When male and female come together in love and understanding, they form the image of God, so Campbell claims.

I found this to be an enlightening quote. Again, Campbell claims that problems within experience (here, within relationship) come from a restriction of consciousness. It is ignorance that dims the beauty of the world around us. This calls to my mind two different quotes.

Rainer Maria Rilke:

Jesus:

I've been thinking a lot about these recently. The majority of our conscious existence is spent simply perceiving. How we perceive affects deeply everything that we do, and thus, what happens to humanity. Human history is the record of what people did because of how they perceived the world around them.

Campbell says the hero is the one who has come to know, but perhaps even more fundamentally, the hero is the one who has come to see.

3. Woman as the Temptress

As the reverse of the goddess, woman can also be temptresses in mythological stories. I think this is the source of many a misunderstanding of myth and, in some cases, has led to the mistreatment of women in history. I believe that women (as well as men) portrayed in negative light in stories should be interpreted as forces and as manifestations of threats within the particular situation of the story, not as guiding commentary on how they actually are or should be treated. The tempting women sent to St. Bernard in Campbell's telling, clearly should not be interpreted as "women are evil" which is clearly a logical fallacy, but as situational threats/obstacles that St. Bernard had to navigate. Clearly, not everyone is vexed with the trouble of having to constantly turn down overly zealous attractive women.

Fascinatingly, I believe I found the best quotes from this section to be outside the section's topical focus. For instance:

The cycle complete, the hero is now in the father's place, he has become what he once found, at least in Campbell's archetypal tongue, to be his nemesis, his opposite. Yet, this is come to after a journey in which his understanding of the universe around him has shifted. So, for us, to truly be in possession, enjoyment and full knowledge of life, we must bypass competency tests that come in many different forms.

Lastly, from this section, I loved this quote, I'm afraid I've already talked quite a bit about similar subjects, but I still find it absolutely appealing as a conceptual reading of human affairs:

Wow. There it is in full. Granted, it's nice to have a grasp of the central aspect of our problems, but it may seem absurdly general and generic when applied to specific situations, "Oh! That's why I lost my job and my wife left me: My consciousness is restricted! Man... I should do something about that." Yeah, you probably should. Or, "Oh! That's why Hitler massacred millions of Jews and why we dropped some nukes on Japan: Ignorance! Boy... We should make sure nothing like that every happens again."

Now, I actually like this a lot and I find it to have some deep truth to it, but, again, it hardly qualifies as practical advice. We must raise our consciousnesses and be not ignorant. But, I must say, there's something to generalist advice like that. Because, applying it at the specific level hardly works, but when we step back and look at the big picture, it makes sense. In figure drawing, this happens frequently. If you're too close to your pad of paper, you may be shading all the areas nicely, but at the end you might step back and find that the head is too small and the right arm too long, and the hips too thin and the foot too small and etc. One must constantly step away from the drawing, away from the canvas, away from the everyday fabric of life, to see how the whole structure of the work is flowing and then make proper adjustments. Otherwise, without regularly being conscious about the whole structure of your art or life, you risk its immanent deformation. So, I guess, how do you do this with life itself? I suppose Campbell would say via myth. Religion serves this purpose for many people, it gives them a way to investigate how to form the whole structure of their lives to make sure that it is, in the end, good.

4. Atonement with the Father

This is a wonderful section. It seems to breath a lot about how one must humble himself to become what he desires to be.

It seems our maturity comes from eliminating the black and white reading of the world for a gentler understanding of the fullness, with beauty, humor and tragedy of life. I found the stories and examples in this section to be most illustrative and helpful, though, sometimes, disconcerting.

In particular, the stories about the Australian Great Father Snake rituals were rather difficult for me to read at times. The drinking of blood and then the slitting of the bottom of the penis to become the image of androgenic god, with both the phallic and vaginal portions represented on the body. Being a highly visual and experiential person, it is difficult to read without imagining BEING a part of such a ritual. Anyway. I found it extremely interesting, but also perhaps a little much. Maybe we lack sufficient ritual in our society, but maybe we don't have to quite have that much, either.

I very much enjoyed the story of Phaethon. That has always been one of my favorite stories from Greek mythology. How bold, and yet how sad. There's something beautiful in the image of his falling, burning, from the chariot. But, as Campbell points out, here is a good reason for the tests and trials to be in place. If we are not ready for the power handed to us when we come to maturity, then how horrible the fall and commotion that follows. It reminds me of an excellent Japanese animated film and graphic novel: Akira.

In a future dystopian Neo-Tokyo, where politicians are corrupt, government protesters proliferate, civil unrest is growing and biking gangs rule the streets, supernatural powers are suddenly called forth in the young biker Tetsuo after a chance encounter with a wrinkle-faced child, an escaped subject in a series of military tests on children to develop one with Jedi-like powers as the next step on the evolutionary scale. Tetsuo ransacks the city with his new found powers, yet they quickly metastasize into a nightmarish reality which he no longer can control. All the while, we learn the secret of Akira, a project that back-fired years ago when the military attempted to forcefully control such a power itself.

That's a long aside, but its an epic masterpiece by Katsuhiro Otomo. Both the graphic novels and the animated film are renowned for their technical virtuosity and epic story. It deals with power, science, religion, technology, and human understanding. You should watch the film if you ever have the chance.

After this quote, Campbell has a brief exposition about the book of Job and God's final speech to Job. I found this to be an excellent commentary. As he mentions, God gives no reasons for his actions, but simply accuses Job of claiming to be more just than God. God goes on to magnify his own "Presence" as the core of might and justice. Even though nothing has been explained, per se, Job seems to accept this understanding of the higher Being of God himself and thus is calmed by God's answer. Then he goes about his life and his blessed. Again, it is the raising of one's consciousness through suffering and humility that win the day, not logical proofs or theorems.

Finally, as a summing up of this principle:

The trials are nothing to the world-transforming understanding that comes through atonement with the father.

5. Apotheosis

Apotheosis is, according to my dictionary widget, "The highest point in the development of something; culmination or climax." I found this to be the most thoroughly interesting section. The fascinating part to me is that the climax is not the defeat of the enemy, but the defeat of the self, the point at which the hero comes to true enlightenment. As Campbell writes comparing this to the becoming of the Bodhisattva in Buddhism:

"All things are Buddha-things"; or again (and this is the other way of making the same statement): "All beings are without self."

This is a beautiful passage. "All beings are without self." It is a way to live that is beyond the very classification of selfhood. It seems that at this point, one does not have to fear the loss of his or her identity, because what dwells within and beyond are the same bountiful and beautiful greatness, the point at which one is no longer reigned in by fear or power or suffering or greed. One finds absolution in all by its complete and total unity in a continuous life force.

I admit that I'm getting rather vague here, as Campbell himself does, but it seems to be true of the greatest and most compelling stories. Christ dies, and suddenly, Christ is everywhere and in everyone. If the hero attains less than the transcendence, then it seems he is not a true hero after all.

This has made me start to consider the films and stories and books which I find most compelling, and, indeed, in most of them, the protagonist comes to a point at which he has a kind of enlightenment that springs him beyond what he knew before, that allows him to love all things around and about him. Yet, in the mythological stories, it seems that this transformation is a total kind of mastery of the universe, while as in life, it seems it is something perhaps as profound, but quieter. We don't get halos, but we do get understanding and so in as much as it transforms us (now relating back to notions about sight) it transforms how we see and comprehend the universe. Thus, for the transcendent hero, the universe itself has been completely shifted and raised to a higher aesthetic level.

In The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoevsky and in Anna Karenina by Tolstoy, similar transformations seem wrought in the respective protagonists, Alexei and Levin. Childhood beliefs about the nature of sainthood are shattered for Alexei, but he finds new strength to leave the monastic community he's basically interned with and face the world in a new way, but with an outgoing love for all. Levin, too, struggles continually with his understanding of love, life, God and the universe, but he comes to a point of satisfaction where he finds himself in tune with it and the universe beautiful in and of itself. What I really love about both of these characters is how they find ways to spin this kind of new understanding into the realm of everyday life. For instance, Anna Karenina ends with Levin's bliss:

Levin realizes that it is something that has been somehow in him the whole time, a golden ball hidden in the cleft of his mind. But, now that he's found it, he also realizes that life will continue to be the same in much of its structure, but that he can and will change dramatically because of his own awareness. I think many people experience a brief inkling of what this kind of sight is like from time to time, but too often it is treated as a kind of game of endurance where one must walk on eggshells holding this glowing golden stuff, to keep it all in perfect balance so as not to lose that one ounce of beautiful understanding. In truth, it seems this kind of holy sight should become an integral part of the hero, of the person and it should be able to be integrated into daily life. Such that all things, "become Buddha things."

Similarly, Campbell writes:

It is the treasure that becomes part of us by our very awareness.

Lastly, in this section, Campbell makes some recourse to warn about pitfalls about misunderstandings about myths, and ways we can misinterpret and misapply them:

I have to say that I agree with Campbell. Too often, this is the case in how we interpret and apply religious thought and belief. Rather than it becoming the way to unite and redeem and purify the world, it becomes a way to divide and polarize it. The mistake is simple, but insidious, as it is indeed the opposite of the hero's goal, but occurs when even the slightest misunderstanding is applied. We can flesh this part out more in comments as well, if needed.

6. The Ultimate Boon

I thought Campbell touched upon an insightful distinction in this portion:

Humor provides personality and a kind of aesthetic taste, something that helps truly bring the world to life. It's fascinating to pit mythology against theology. I'm not sure that they have to be in conflict. But I can see how their different moods/sentiments allow for vastly different readings of life.

Finally, back to the understanding of what the hero's quest and focus actually is: heightened understanding and awareness about the universe:

I like his list of helping activities, though I feel as though each of these also have within them the duality that allows one to become trapped. "Art, literature, myth and cult, philosophy, and ascetic disciplines" if treated like the recently mentioned "literal-minded and sentimental theology" then we just end up trapped in ourselves and our own systems of heuristics, rather than seeking the knowledge that comes from real experience of the totality and beauty of life. To that effect, these things can only help one so far before he must put down his book and leave his arm chair or cave (as in the ascetic) and journey beyond his front door step. It makes me think of The Hobbit. But, I'll just leave off with that, assuming you've probably read it and know the sense I mean.

There is so much in this chapter, that I feel somewhat daunted at the idea of summing up my thoughts on it. I admit that the last two sections are my favorite with the second and third not too far behind. I'll deal out by sub-chapters centering discussion around quotes from Campbell.

1. The Road of Trials

Though this section helped set up the rest of the chapter, I feel as though this was also perhaps the least interesting of the subsections. After opening the chapter, Campbell recounts the tale of Psyche's trials to gain Cupid. This portion reminded me of reading C.S. Lewis' Till We Have Faces, the other year, and what an excellent and fascinating a reshaping of the myth it was. That's a bit of an aside. From Campbell's description, we understand the gist: hero's go through trials and tests to attain their goals.

Despite the simple transfer of information about hero's trials, I found several of Campbell's claims rather fascinating, for one the following concerning medicine men:

The medicine men, therefore, are simply making both visible and public the systems of symbolic fantasy that are present in the psyche of every adult member of their society. "They are the leaders in this infantile game and the lightning conductors of common anxiety. They fight the demons so that others can hunt the prey and in general fight reality."

Who are our "medicine men" today? Who among us "fight the demons" so that we may "fight reality?" I suppose one could argue that preachers and religious teachers might play a similar role, but I feel they're role has shifted over the years out of this dramatic category of action, and more into the role of the helper, of the guide attempting to help point people in the right direction when they feel confused. Also, religious concerns have branched in the modern age, and now often include the questions of the religion's validity. I think this has largely occurred because knowledge about other religions and about explanations of how the natural world work have been cast, by some, into contention with how one views the structure and validity of his religious beliefs.

I am aware that there have been dissidents of religious factuality in all ages, with recorded skepticism coming from as far back as the pre-Socratic philosophers. But, I also feel as though this trend has come to a head since the Enlightenment. Because scientific systems of thought have been so highly prized, there has been an attempt to require of religious belief the same structure of empirical evidence to prove its "truth." Some have attempted to answer this challenge by advancing a system of admitted irrationality, claiming it is faith itself in the face of reason that is the heart of true belief. Yet, this seems to miss the point, as it attempts to play in a league it was never supposed to be in, like a dance team being forced to play football to prove they are good dancers. It's nonsensical. Campbell's argument, on the other hand, is that the stories were never meant to be taken factually, because they hold implications for how we should live, rather than indications of what exactly did or did not occur in antiquity. I must say that I find this point rather compelling.

On to the next fascinating quote:

And so it happens that if anyone–in whatever society–undertakes for himself the perilous journey into the darkness by descending, either intentionally or unintentionally, into the crooked lanes of his own spiritual labyrinth, he soon finds himself in a landscape of symbolical figures (any one of which may swallow him) which is no less marvelous than the wild Siberian world of the pudak and sacred mountains. In the vocabulary of the mystics, this is the second stage of the Way, that of the "purification of the self," when the senses are "cleansed and humbled," and the energies and interests "concentrated upon transcendental things"; or in the vocabulary of more modern turn: this is the process of dissolving, transcending, or transmuting the infantile images of our personal past.

Campbell returns again and again to this image of the myth as a spiritual guidepost, a language for encountering and moving through life. Though the process seems one that is, in many ways, intellectual and introverted in our society, he frames it within epic proportions. I say that I rather agree with Campbell's mentality. Finding one's place in life seems to be a steady adventure in the interior of soul, no matter the level of physical activity involved.

One descends into the self to encounter and move past self. This is a central motif of the chapter, the kind of "second birth" that takes place within one to reach a new level of maturity.

Finally, the following quote seems to sum up very well the first section and set the tone/theme for the rest of the chapter with the claim of the cyclical realization of oneness within duality:

The hero, whether god or goddess, man or woman, the figure in a myth or the dreamer of a dream, discovers and assimilates his opposite (his own unsuspected self) either by swallowing it or by being swallowed. One by one the resistances are broken. He must put aside his pride, his virtue, beauty, and life, and bow or submit to the absolutely intolerable. Then he finds that he and his opposite are not of differing species, but one flesh.

This makes me wonder about our interpretations of spiritual rebirth within the church. So often the dialogue centers on rejecting an old self, a kind of aggressive pushing away of a past or a still disappointing present self, rather than a whole and full acceptance of a new self. The kind of death and birth of Christ himself, one where the hero is led silently to the slaughter. He allows himself to be subsumed and in this obedience, this emptying of self, he achieves a new grasp and way of life itself. It is a the true union within the self that is important. More on this in Apotheosis.

2. The Meeting with the Goddess

As the hero continues through his trials, he is sure to meet the goddess. Campbell claims she is the symbol of the remembered mother and the future bride. She can be kind or she can be fearful, she helps either bring together life or destroy it.

Woman, in the picture language of mythology, represents the totality of what can be known. The hero is the one who comes to know. As he progresses in the slow initiation which is life, the form of the goddess undergoes for him a series of transfigurations: she can never be greater than himself, though she can always promise more than he is yet capable of comprehending. She lures, she guides, she bids him burst his fetters. And if he can match her import, the two, the knower and the known, will be released from every limitation.

Woman, in mythology, as gateway to freedom and universal comprehension. This again fits with the theme of freedom and oneness in duality in the last quote from Road of Trials. When male and female come together in love and understanding, they form the image of God, so Campbell claims.

Woman is the guide to the sublime acme of sensuous adventure. By deficient eyes she is reduced to inferior states; by the evil eye of ignorance she is spellbound to banality and ugliness. But she is redeemed by the eyes of understanding. The hero who can take her as she is, without undue commotion but with the kindness and assurance she requires, is potentially the king, the incarnate god, of her created world.

I found this to be an enlightening quote. Again, Campbell claims that problems within experience (here, within relationship) come from a restriction of consciousness. It is ignorance that dims the beauty of the world around us. This calls to my mind two different quotes.

Rainer Maria Rilke:

If your daily life seems poor, do not blame it; blame yourself, tell yourself that you are not poet enough to call forth its riches; for to the creator there is no poverty and no indifferent place.

Jesus:

The eye is the lamp of the body. If your eyes are good, your whole body will be full of light. But if your eyes are bad, your whole body will be full of darkness. If then the light within you is darkness, how great is that darkness.

I've been thinking a lot about these recently. The majority of our conscious existence is spent simply perceiving. How we perceive affects deeply everything that we do, and thus, what happens to humanity. Human history is the record of what people did because of how they perceived the world around them.

Campbell says the hero is the one who has come to know, but perhaps even more fundamentally, the hero is the one who has come to see.

3. Woman as the Temptress

As the reverse of the goddess, woman can also be temptresses in mythological stories. I think this is the source of many a misunderstanding of myth and, in some cases, has led to the mistreatment of women in history. I believe that women (as well as men) portrayed in negative light in stories should be interpreted as forces and as manifestations of threats within the particular situation of the story, not as guiding commentary on how they actually are or should be treated. The tempting women sent to St. Bernard in Campbell's telling, clearly should not be interpreted as "women are evil" which is clearly a logical fallacy, but as situational threats/obstacles that St. Bernard had to navigate. Clearly, not everyone is vexed with the trouble of having to constantly turn down overly zealous attractive women.

Fascinatingly, I believe I found the best quotes from this section to be outside the section's topical focus. For instance:

The mystical marriage with the queen goddess of the world represents the hero's total mastery of life; for the woman is life, the hero its knower and master. And the testings of the hero, which were preliminary to his ultimate experience and deed, were symbolical of those crises of realization by means of which his consciousness came to be amplified and made capable of enduring the full possession of the mother-destroyer, his inevitable bride. With that he knows that he and the father are one: he is in the father's place.

The cycle complete, the hero is now in the father's place, he has become what he once found, at least in Campbell's archetypal tongue, to be his nemesis, his opposite. Yet, this is come to after a journey in which his understanding of the universe around him has shifted. So, for us, to truly be in possession, enjoyment and full knowledge of life, we must bypass competency tests that come in many different forms.

Lastly, from this section, I loved this quote, I'm afraid I've already talked quite a bit about similar subjects, but I still find it absolutely appealing as a conceptual reading of human affairs:

Nevertheless, every failure to cope with a life situation must be laid, in the end, to a restriction of consciousness. Wars and temper tantrums are the makeshifts of ignorance; regrets are illuminations come too late.

Wow. There it is in full. Granted, it's nice to have a grasp of the central aspect of our problems, but it may seem absurdly general and generic when applied to specific situations, "Oh! That's why I lost my job and my wife left me: My consciousness is restricted! Man... I should do something about that." Yeah, you probably should. Or, "Oh! That's why Hitler massacred millions of Jews and why we dropped some nukes on Japan: Ignorance! Boy... We should make sure nothing like that every happens again."

Now, I actually like this a lot and I find it to have some deep truth to it, but, again, it hardly qualifies as practical advice. We must raise our consciousnesses and be not ignorant. But, I must say, there's something to generalist advice like that. Because, applying it at the specific level hardly works, but when we step back and look at the big picture, it makes sense. In figure drawing, this happens frequently. If you're too close to your pad of paper, you may be shading all the areas nicely, but at the end you might step back and find that the head is too small and the right arm too long, and the hips too thin and the foot too small and etc. One must constantly step away from the drawing, away from the canvas, away from the everyday fabric of life, to see how the whole structure of the work is flowing and then make proper adjustments. Otherwise, without regularly being conscious about the whole structure of your art or life, you risk its immanent deformation. So, I guess, how do you do this with life itself? I suppose Campbell would say via myth. Religion serves this purpose for many people, it gives them a way to investigate how to form the whole structure of their lives to make sure that it is, in the end, good.

4. Atonement with the Father

This is a wonderful section. It seems to breath a lot about how one must humble himself to become what he desires to be.

Atonement (at-one-ment) consists in no more than the abandonment of that self-generated double monster–the dragon thought to be God (superego) and the dragon thought to be Sin (repressed id). But this requires an abandonment of the attachment to the ego itself, and that is what is difficult.

It seems our maturity comes from eliminating the black and white reading of the world for a gentler understanding of the fullness, with beauty, humor and tragedy of life. I found the stories and examples in this section to be most illustrative and helpful, though, sometimes, disconcerting.

In particular, the stories about the Australian Great Father Snake rituals were rather difficult for me to read at times. The drinking of blood and then the slitting of the bottom of the penis to become the image of androgenic god, with both the phallic and vaginal portions represented on the body. Being a highly visual and experiential person, it is difficult to read without imagining BEING a part of such a ritual. Anyway. I found it extremely interesting, but also perhaps a little much. Maybe we lack sufficient ritual in our society, but maybe we don't have to quite have that much, either.

I very much enjoyed the story of Phaethon. That has always been one of my favorite stories from Greek mythology. How bold, and yet how sad. There's something beautiful in the image of his falling, burning, from the chariot. But, as Campbell points out, here is a good reason for the tests and trials to be in place. If we are not ready for the power handed to us when we come to maturity, then how horrible the fall and commotion that follows. It reminds me of an excellent Japanese animated film and graphic novel: Akira.

In a future dystopian Neo-Tokyo, where politicians are corrupt, government protesters proliferate, civil unrest is growing and biking gangs rule the streets, supernatural powers are suddenly called forth in the young biker Tetsuo after a chance encounter with a wrinkle-faced child, an escaped subject in a series of military tests on children to develop one with Jedi-like powers as the next step on the evolutionary scale. Tetsuo ransacks the city with his new found powers, yet they quickly metastasize into a nightmarish reality which he no longer can control. All the while, we learn the secret of Akira, a project that back-fired years ago when the military attempted to forcefully control such a power itself.

That's a long aside, but its an epic masterpiece by Katsuhiro Otomo. Both the graphic novels and the animated film are renowned for their technical virtuosity and epic story. It deals with power, science, religion, technology, and human understanding. You should watch the film if you ever have the chance.

The problem of the hero going to meet the father is to open his soul beyond terror to such a degree that he will be ripe to understand how the sickening and insane tragedies of this vast and ruthless cosmos are completely validated in the majesty of Being. The hero transcends life with its particular blind spot and for a moment rises to a glimpse of the source. He beholds the face of the father, understands–and the two are atoned.

After this quote, Campbell has a brief exposition about the book of Job and God's final speech to Job. I found this to be an excellent commentary. As he mentions, God gives no reasons for his actions, but simply accuses Job of claiming to be more just than God. God goes on to magnify his own "Presence" as the core of might and justice. Even though nothing has been explained, per se, Job seems to accept this understanding of the higher Being of God himself and thus is calmed by God's answer. Then he goes about his life and his blessed. Again, it is the raising of one's consciousness through suffering and humility that win the day, not logical proofs or theorems.

Finally, as a summing up of this principle:

For the son who has grown really to know the father, the agonies of the ordeal are readily borne; the world is no longer a vale of tears but a bliss-yielding, perpetual manifestation of the Presence.

The trials are nothing to the world-transforming understanding that comes through atonement with the father.

5. Apotheosis

Apotheosis is, according to my dictionary widget, "The highest point in the development of something; culmination or climax." I found this to be the most thoroughly interesting section. The fascinating part to me is that the climax is not the defeat of the enemy, but the defeat of the self, the point at which the hero comes to true enlightenment. As Campbell writes comparing this to the becoming of the Bodhisattva in Buddhism:

"All things are Buddha-things"; or again (and this is the other way of making the same statement): "All beings are without self."

The world is filled and illumined by, but does not hold, the Bodhisattva ("he whose being is enlightenment"); rather, it is he who holds the world, the lotus. Pain and pleasure do not enclose him, he encloses them–and with profound repose.

This is a beautiful passage. "All beings are without self." It is a way to live that is beyond the very classification of selfhood. It seems that at this point, one does not have to fear the loss of his or her identity, because what dwells within and beyond are the same bountiful and beautiful greatness, the point at which one is no longer reigned in by fear or power or suffering or greed. One finds absolution in all by its complete and total unity in a continuous life force.

I admit that I'm getting rather vague here, as Campbell himself does, but it seems to be true of the greatest and most compelling stories. Christ dies, and suddenly, Christ is everywhere and in everyone. If the hero attains less than the transcendence, then it seems he is not a true hero after all.

This has made me start to consider the films and stories and books which I find most compelling, and, indeed, in most of them, the protagonist comes to a point at which he has a kind of enlightenment that springs him beyond what he knew before, that allows him to love all things around and about him. Yet, in the mythological stories, it seems that this transformation is a total kind of mastery of the universe, while as in life, it seems it is something perhaps as profound, but quieter. We don't get halos, but we do get understanding and so in as much as it transforms us (now relating back to notions about sight) it transforms how we see and comprehend the universe. Thus, for the transcendent hero, the universe itself has been completely shifted and raised to a higher aesthetic level.

In The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoevsky and in Anna Karenina by Tolstoy, similar transformations seem wrought in the respective protagonists, Alexei and Levin. Childhood beliefs about the nature of sainthood are shattered for Alexei, but he finds new strength to leave the monastic community he's basically interned with and face the world in a new way, but with an outgoing love for all. Levin, too, struggles continually with his understanding of love, life, God and the universe, but he comes to a point of satisfaction where he finds himself in tune with it and the universe beautiful in and of itself. What I really love about both of these characters is how they find ways to spin this kind of new understanding into the realm of everyday life. For instance, Anna Karenina ends with Levin's bliss:

'This new feeling hasn't changed me, hasn't made me happy or suddenly enlightened, as I dreamed – just like the feeling for my son. Nor was there any surprise. And faith or not faith – I don't know what it is – but this feeling has entered into me just as imperceptibly through suffering and has firmly lodged itself in my soul.

'I"ll get angry in the same way with the coachman Ivan, argue in the same way, speak my mind inappropriately, there will be the same wall between my soul's holy of holies and other people, even my wife, I'll accuse her in the same way of my own fear and then regret it, I"ll fail in the same way to understand with my reason why I pray, and yet I will pray – but my life now, my whole life, regardless of all that may happen to me, every minute of it, is not only not meaningless, as it was before, but has the unquestionable meaning of the good which it is in my power to put into it!'

Levin realizes that it is something that has been somehow in him the whole time, a golden ball hidden in the cleft of his mind. But, now that he's found it, he also realizes that life will continue to be the same in much of its structure, but that he can and will change dramatically because of his own awareness. I think many people experience a brief inkling of what this kind of sight is like from time to time, but too often it is treated as a kind of game of endurance where one must walk on eggshells holding this glowing golden stuff, to keep it all in perfect balance so as not to lose that one ounce of beautiful understanding. In truth, it seems this kind of holy sight should become an integral part of the hero, of the person and it should be able to be integrated into daily life. Such that all things, "become Buddha things."

Similarly, Campbell writes:

Those who know, not only that the Everlasting lives in them, but that what they, and all things, really are is the Everlasting, dwell in the groves of the wish-fulfilling trees, drink the brew of immortality, and listen everywhere to the unheard music of eternal concord.

It is the treasure that becomes part of us by our very awareness.

Lastly, in this section, Campbell makes some recourse to warn about pitfalls about misunderstandings about myths, and ways we can misinterpret and misapply them: